The Livingston County Historical Society’s museum, the Livingston County Museum, looks a little different from what I remember when I interned there several years ago.

Back then, it looked like a cross between a museum and your grandparent’s attic.

To be sure, there were a few well-curated, permanent exhibits. (All the exhibitions I mention here can still be found in the museum today.) For example, Always About the Land introduces Livingston County’s history, particularly its agrarian past and present. Schoolhouse Days comprises artifacts and photos related to education in the county, including stories about the museum’s largest artifact—its building. The LCHS has resided in the former Geneseo District #5 cobblestone schoolhouse at 30 Center Street in Geneseo, NY, since 1932. The Home and Hearth room is still my favorite. The exhibition primarily shows objects related to the 19th-century woman’s “sphere” of home and housework, with a giant loom, spinning wheel, cookware, and brick fireplace. The big windows in the room overlook the schoolhouse’s sprawling yard and have always made the space seem brighter, calmer, and extra special to me.

Otherwise, the place was a smorgasbord of old stuff. Every spot seemed filled with something, save for a pathway through the building. Most things were grouped by type and came in multiples. There was clothing, artwork, furniture, photographs, dinnerware, business advertisements, hand tools, large farming instruments, a piece of a wooden water pipe dug up from under Main Street in Geneseo (seriously!), guns, swords, arrowheads, musical instruments, medical instruments (I could go on), all out on display with little captions explaining what they were and where they came from. It was a lot. In its seemingly infinite variety, the museum could be hard to understand and challenging to navigate.

I don’t want anyone to get the wrong idea. I adore the Livingston County Historical Society (LCHS). It has a lot of community spirit embedded in it. You can feel it in every corner of the museum, even in the parts that look a little less refined.

The reality is that the stuff in the museum came from people who gave their personal and perhaps extremely meaningful items to their county’s historical society. Subsequently, other community members volunteered their time to acknowledge those contributions, create captions for the items, and place them on display with other similar things so that grandma’s favorite doll could be appreciated amongst other cherished toys, and grandpa’s legendary snowshoes were showcased with someone else’s lucky fishing pole. I am generally fond of people coming together in good faith to contribute to the history of where they live.

Another reality must be acknowledged: running a local history organization takes work and resources. In the United States, many rely on volunteers and operate with limited funds, resulting in general anxiety about sustaining the community support, trust, and attention needed to keep going. And yet, the LCHS has been in existence since 1876. At nearly 150 years old, it is one of the oldest county historical societies in New York State. The LCHS has operated a museum since 1896. Its first museum building, a log cabin, still stands in its original location just off Main Street in Geneseo.

Like any organization, the LCHS has had its ups and downs over the years. From my vantage point as a student intern in 2014-2015, the museum seemed to be on an upswing. At the time, there was a determination to make the LCHS “better” and more professional-looking, particularly by curating more exhibitions and improving facilities for welcoming people and preserving the collection. The engine for these changes was the LCHS’s Museum Administrator (and only paid employee), Anna Kowalchuk (pronounced Ah-na). With her conviction, perseverance, and sense of humor, Anna made me, and many others, believe that this little museum might actually get to the mountaintop of its ambition. Exhibitions like Always About the Land, Schoolhouse Days, and Home and Hearth were part of this journey to a different, reinvented LCHS. There was more to come.

Of course, I couldn’t stay. At the time of my internship, I was in my senior year at SUNY Geneseo and focused on pursuing a career as an archivist after graduation. My internship with LCHS that school year was a way to add to my experience in archival work and boost my graduate school applications. Anna was endlessly supportive of my career goals and the intensity with which I pursued them. I think she was also somewhat amused that I included my humble, rural college-town historical society on my way to getting my foot in the door at some snazzy, big-city museum. Whether she was making a bespoke mannequin out of a pillow and duct tape or demonstrating how to use a floppy, plastic ruler to carefully unstick old photographs unsuitably adhered to a piece of poster board, Anna made sure to inform me that “this is how they do it at the Met.” This line still cracks me up to this day!

In 2015, I graduated with a BA in History. After a summer archives internship in Everglades National Park, I enrolled in the Dual Master’s program in Library Science and History at Queens College—CUNY in the fall. I drove from the tip of Florida to Queens for orientation. I was 22 years old, I didn’t have anywhere to live yet, and I knew very few people in New York City, having lived in upstate New York all my life (very cliché, I know). I eventually found an apartment in Queens, made new friends, and settled into the rhythm of going to school full-time and working part-time. In 2018, I graduated from Queens College with an MA in History and an MLS with a Certificate in Archives and the Preservation of Cultural Materials. I now work professionally as an archivist at the American Folk Art Museum in New York City, managing its institutional records and archival special collections related to the history of folk art and self-taught art. I now have colleagues at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and other cultural heritage and academic institutions nationwide.

SUNY Geneseo, May 2015

December 2016

Mark Morris Dance Group Archives,

February 2018

Queens College, June 2018

April 2021

All this time, I remembered the LCHS. I kept in touch with Anna when I could and followed along with the museum on social media. Only in the last few years have I been back inside, and what I see is inspiring.

The museum has a beautiful new accessible entrance and lobby with a wheelchair ramp and renovated bathroom facilities. Previously, entering the building and using the restroom required navigating steps and a narrow hallway. Now, the museum shows it when it says, “Welcome!”

A few new exhibitions are inside, but I am most excited about the one entitled The Big Tree of the Genesee. The show features the museum’s section of the (in)famous Big Tree, a massive oak that once stood on the banks of the Genesee River in Geneseo and near the site where the Big Tree Treaty of 1797 was finalized. Contrary to popular belief (I admit I got this wrong for many years), this agreement gets its title not from the size of this tree but from the name of the Seneca village that existed near present-day Geneseo— “Big Tree.” Ultimately, the Big Tree Treaty dispossessed the indigenous Seneca of much of their territory in present-day western New York. In sum, 3.5 million acres of land west of the Genesee River to the Great Lakes were green-lit to be settled by white people in exchange for $100,000 and 200,000 acres across eleven reservations.1 For many years the tree artifact had been stored in a small outdoor enclosure on the museum grounds, out of the way of most visitors and semi-susceptible to the elements. It makes me very happy that it is now inside, conserved, and activated as the focal point of an exhibition that tells a more nuanced story of Big Tree, including information about the ecology of the local area, the past and present-day contributions that the Seneca Nation has made to steward the land, and the disastrous effects that the Treaty and white settlement, more broadly, has had on indigenous communities in the region.2

Last year, I toured the LCHS again with Anna. After we passed the Big Tree, we stopped in the doorway leading to a large room called the Memorial Room. The Memorial Room and its adjoining room, the Annex, are the museum’s rear rooms.

“This room probably looks familiar to you,” Anna said.

It certainly did. The objects and overall layout of the Memorial Room seemed virtually unchanged from seven years ago. The antique toys were in a display cabinet on the right. The salt mining artifacts were centered at the entrance in another display case. Along the wall to the left (among other pieces of furniture) was the absurdly large desk that had belonged to some presumably important person. The middle of the room was essentially inaccessible, serving as a parking lot for objects that didn’t have a place along the path around the edge of the room. Indeed, this was the attic aesthetic I remembered from years ago.

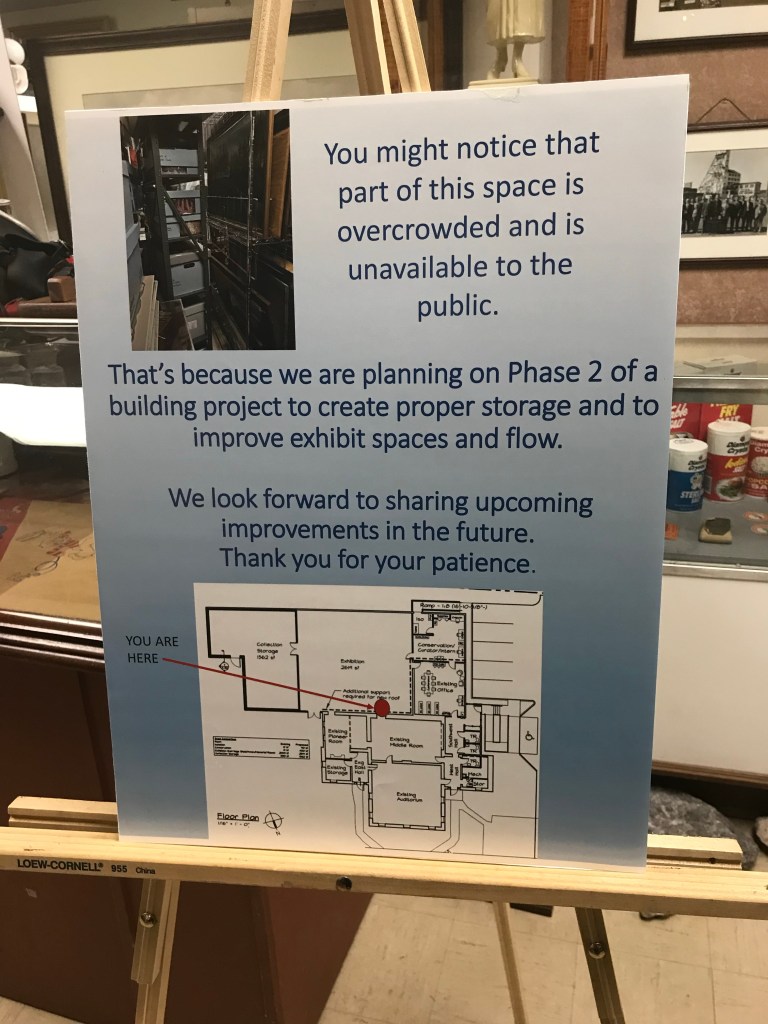

The one new thing was the signpost in the doorway.

“This is our plan for this space,” Anna noted, referring to the sign. “All of this is going to be gone.” She gestured with her arms, drawing an imaginary circle around the room. I listened as she explained further.

The Memorial Room and the Annex would be emptied and ultimately torn down. Due to their construction and layout, these rooms were not ideal for displaying and storing objects. Moreover, they were not original to the historic schoolhouse building anyway. In their place, a brand-new exhibition space and a climate-controlled collections storage and handing area were to be built. These new additions would provide a more cohesive space for exhibitions, and, most significantly, they would give the museum the ability to put objects away in a safe storage space rather than crowding the rooms.

This plan seemed to be the most monumental step yet toward bringing the Museum closer to its goal of improving its facilities, exhibitions, and educational offerings. It was what Anna and the LCHS’s volunteers and supporters had been working so hard for. They had a blueprint and were working on gaining the funds to execute it. Anna said she had a meeting with the architects in the coming days.

I was so proud.

The LCHS had come a long way, and while there was still so much to do, the future looked very bright. Standing there next to Anna, looking at the organized chaos of the Memorial Room, I imagined the new possibilities ahead for the historical society. There would be new grant funding prospects to support the museum’s programs and collection. The new space would make more room for featuring untold stories about the county’s past. And, most certainly, there would be more opportunities for new generations of students to learn and grow by examining and stewarding history up close.

I said, “Anna, this is going to change everything.”

“I know,” she replied. “It really will.”

Notes:

- For an overview of and recommendations for additional source material about the Big Tree Treaty, I recommend checking out historian Michael Oberg’s blog, specifically his post “The Treaty of Big Tree–Let’s Follow the Money” from 2017.

- Livingston County News covered the work to study and conserve the Big Tree in 2017. In this video, you can see the structure where the tree used to be housed.

Leave a comment